What municipalities can learn from New York’s distinctive street furniture

The atmosphere of a location is built by a thousand small details. Some of it comes down to geography: the quality of light, plants in the ecosystem, and movement of air.

A city’s personality is also made of the materials and design of buildings, common spaces, attractions, and amenities. What would London be without double decker buses? Or Hong Kong without junks in the harbor?

New York has many large iconic buildings—from the unsurpassed art deco of the Chrysler and Empire State buildings to the historic Brooklyn Bridge. Yet New York is also built on smaller scale design. Consider the green metal enclosures emblazoned with bright circles at subway stations; the sidewalk cellar doors that open onto steep ladder-like stairs; the iconic urban benches that dot Central Park. Many of these small details arise from municipal laws, infrastructure, and volume purchasing. Although they may seem like small or practical details when they’re first installed, the look that arises from these choices shape the city for generations.

When small municipalities today are looking at the requisition of street furniture, their choices will similarly echo into the future, creating ambience and place that brands their city, as it grows.

Urban benches: social, cultural, and aesthetic

Outdoor benches are a central part of an urban identity. By having well-placed benches, the city invites people out onto the street. Vibrant street culture creates a metro’s character.

Research has shown the presence of comfortable benches helps mental, physical, and social health, and the continuing popularity of dedicated or commemorative benches shows that people agree. People love street furniture that makes a city into a home.

Seating is also a powerful tool for creating social landscape. A municipality that invites people to gather and interact is engaged in placemaking with their community. Such great spaces often attract tourism and clients to local businesses for a vibrant, engaged streetscape.

Bench design offers a hint of the character of a city. Are the benches artistic, plain, classical, or modern? Is the design hostile to some, or inviting to all? Where are the benches placed in relation to gathering places, amenities, and facilities?

New York’s bench designs

New York: densely packed, rich in history, and diverse. Yet very livable: NYC invites people to live in the public sphere. It can set example to other municipalities. Local government offers a “CityBench” program that invites the public to suggest locations for new bench installations. The program especially prioritizes transit areas, sidewalks near transit, and centers of activity: commercial districts, community centers, seniors’ centers, and other facilities. The ubiquity of benches in New York helps it invite people of all ages and abilities out onto its streets.

The World Fair bench

New York city has several popular urban bench styles, but the World Fair bench is one of the two most iconic.

Robert Moses, a city parks commissioner in the 30s, wanted to develop an aesthetic that would tie the look of the city together, throughout its many parks. He commissioned a bench design to be created for the 1939 World’s Fair. This “World’s Fair Bench” is found in formal areas in Central Park, as well as notable installations in Washington Square, Lindsay East River, and Bryant parks. The benches are also a place to rest on the boardwalks along Coney Island, Roosevelt Island, and the North Cove Marina. The precise geometry of the circular arms and half-circular feet reflect the art deco aesthetic popular at the time.

In Central Park, the wood on these benches is often painted green, but plain or stained wood is common in other locations. Original styles feature an X of bracing metal strips across the back.

The Chrystie-Forsythe bench

Also developed in the 1930s was the “Christie Forsythe” (Chrystie-Forsythe) bench, known sometimes only as the “wood-and-concrete” bench. This urban bench is seen all over Central Park.

The NYC Parks board link suggests that “Christie Forsythe” is the correct spelling but does not offer provenance of the name. One prominent location featuring this concrete bench is at Sara D. Roosevelt Park, opened in 1934, between Chrystie St. and Forsythe St. in the Lower East Side. It is possible that the bench was originally developed for or installed at this site and that is where the name comes from. In that case, Chrystie should contain a “y.”

Examples are found in other parks opened during the mid-thirties, like Orchard Beach in the Bronx. Although it is slightly less recognizable than the World Fair bench, it also is dotted around the city.

The Chrystie-Forsythe has a comfortable, laid-back style, often placed in rows so that many people can gather and lounge. The concrete looks like a bracket with a shaped flourish that holds sloped wooden slats. These are occasionally replaced with recycled plastic, but wood is still the most common replacement material.

Custom bench design for your municipality

When creating parks, plazas, or city plans, choosing street furniture and placing it thoughtfully will support shared public experience. You’re inviting your citizens to create connection in common spaces. At Reliance Foundry, our mission is to make places people want to be: a mission shared with most city planners. Our traditional bollard lines have been offered to create walkable, protected pedestrian spaces. We now offer urban benches to enhance those areas. All our benches, like the popular Marietta, are chosen for their strength and appeal. Our unique laser-cut aluminum Austin and Newport benches offer ease of transport and installation, to be easy for crews to dispatch. Want something other than our stock patterns? Get in touch: we can create a custom laser-etched design for your location.

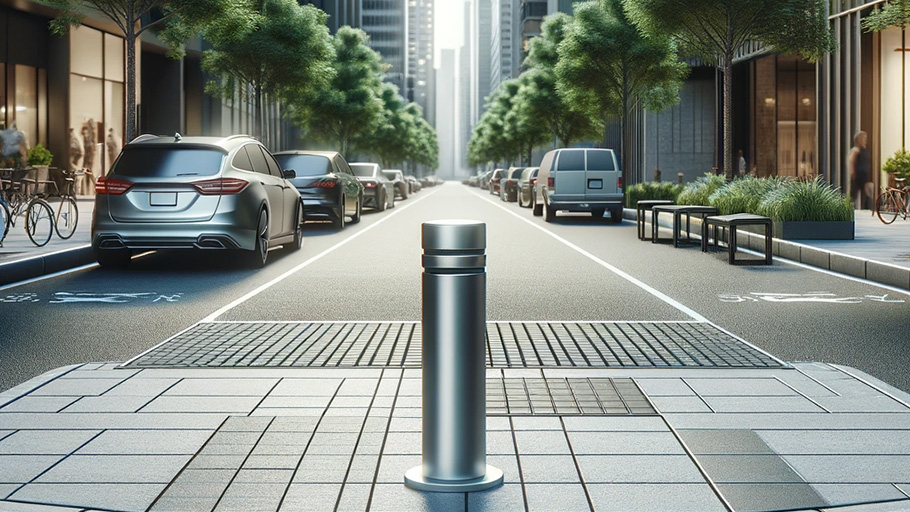

Bollards also support urban identity

Active streets require active transportation options, like bike lanes, pedestrian spaces, and transit. Bike lane bollards are one way cities create dynamic interaction with the streetscape. However, bollards can add to a city with both form and function.

The option to customize bollards, as is very common in the UK, can allow cities to take their branding to a new level.

New York’s bollards—a unique design

Function and form went into the design of some unique New York bollards.

In North America, bollards are often installed to act like a fence, absorbing impact to slow or stop what is striking them. Another type of bollard, the bell bollard, is more common in the close quarters of British roadways. Bell bollards are often placed on tight corners and are designed to redirect energy, rather than stopping it. They catch the errant wheels of a vehicle making a tight turn and they return the vehicle back to the roadway.

Martello bollards are designed to act as both barrier and redirection. In New York, tight turns are less common than on British streets, but traffic density and shared space is a definite challenge. These bollards are therefore designed to both protect pedestrians, as impact absorbing bollards, and to nudge vehicles back to their appropriate places when they wander. Inspired by the densely-walled, protective Martello forts that marked coastal locations across the British Empire, these bollards have a larger profile than a bell bollard. This allows them to stop a vehicle should their directional nudge fail.

These bollards are being installed along areas of heavy traffic and can be seen dotting the Manhattan-side approach to the Brooklyn Bridge.

Overlooked hardscape and municipal law

How a city fulfills the functions of safety, water management, garbage management, transportation, and building codes all contribute to the look and feel of the space. Whether it is customized manhole covers ordered with logos or messages, trench drain bought in bulk for cost savings offering a consistent (and sometimes decorative) aesthetic, or how a city chooses and plants trees, little decisions add up to great character.

A legacy that persists: New York fire escapes

Fire escapes are not street furniture, but in New York they frame and define the architecture in similar ways. These accents also speak to New York’s history.

New York densified quickly. Like other major cities densifying at the time, NYC was filled with tightly-packed wood-framed buildings, each filled with coal-burning cast-iron stoves. The buildings were deeply vulnerable to fire.

In 1776, during the American Revolutionary War, the first of three major fires broke out in the city. Whether purposefully lit as an act of war, or if it was accidental is still a matter of debate. (And if it was an act of war, which side did it benefit most?) Regardless, by the time it the inferno was contained, between 10-25% of the buildings in the city were damaged.

In 1815, bylaws were passed that restricted the creation of wood-framed structure. Even still, the Great Fire of 1835 took out over 600 buildings spanning 17 city blocks. The last great fire, in 1845, was held in check by the fact that many of the structures around it were made of stone or brick.

The possible devastation of these fires in tightly-packed tenements led to a requirement for outdoor fire escapes in the Tenement House Act of 1867. Evolving building codes that include sprinklers and other indoor fire control systems led to this requirement being removed in 1968. They still are a source of identity throughout the city, however. These wrought iron cages affixed to the outside of mid-size brick buildings are a celebrated view of New York. Often the escapes are painted black, but that’s not necessary: the requirement is only that they be painted a “contrasting” color.

Tree grates and tree guards

Like fire escapes, not all site furnishings persist indefinitely. Function and form together brought them into the city, and if they lose function, they will fade away. Another sight being lost on city streets are New York’s tree grates. Once an iconic part of Manhattan’s hardscape, these are ceding in favor of a policy of installing tree guards.

However, some of the allowed guard options echo the wrought iron styles of historical fire escapes. This is one way old designs live on, in new forms and for new functions.

A custom look brands a city

Each piece of New York’s distinctive site furniture was designed for a function. Architectural trends and available materials influenced the style. The choices made influenced the suppliers and builders of infrastructure in New York, so that each design echoes and refracts past its original setting. When these designs get reimagined or restructured over the years—as tastes, style, or materials change—the foundational design can be reinterpreted many times over.

When a small municipality makes a large street furniture or bollard purchase, the city’s look or brand should be part of the decision-making process. What small design elements might echo through a growing city for decades or centuries to come? How will these elements, colors, and materials help shape the experience of the residents and businesses that come to make the city their home?

Reach out to our sales team if you have questions about customization of bollards or benches!