Supporting modern traffic priorities while restoring the nation’s infrastructure

According to a 2019 report from the American Road and Transportation Builders Association, there are 47,000 structurally deficient bridges across the US. A structurally deficient bridge is considered safe for public travel yet needs “urgent repairs.”

To rate a bridge, engineers evaluate the condition of the deck, superstructure, substructure, and culverts. If any area is in “poor” or “worse” condition, then the engineer flags the bridge as in need of urgent attention.

Not all bridge fixes are the same. Of structurally deficient bridges in the US:

- 34% need to be replaced

- 29% need rehabilitation

- 17% need to be widened and rehabilitated

- 5% need deck repair

- and 15% need other structural work

Bridges and traffic management

Bridge reconstruction and widening offers an opportunity to change the design of the bridge deck. Modern transportation plans have a new perspective than those of 40 or more years ago, when many of these bridges were first built. Two notable changes are:

- Increased priority given to public and active transportation (such as cycle commuting).

- Vision Zero programs to limit road traffic fatality.

These contemporary approaches shift perspective on how a bridge might be used.

A footpath over water: pedestrian space on bridges

Bridges primarily designed for vehicle traffic often have a pedestrian walkway. Those in major cities or with beautiful views can become tourist destinations. The view of a skyline and water from mid-bridge is often breathtaking.

Bridges are also an engineering feat that draw attention and excitement. On the Golden Gate Bridge’s opening day in 1937, it was only open to pedestrians. 200,000 people came to walk, run, roller-skate, or unicycle across the 1.7 mile bridge. Time often solidifies the connection between people and local bridges. Fifty years after opening day, 800,000 people showed up to celebrate the anniversary of the Golden Gate Bridge. There were so many that hundreds of thousands were turned away due to weight restrictions.

Bike lanes on bridges

Bike lanes are often controversial on bridges, because there is often very little room to widen the actual bridge deck. Yet modern urban planning often prioritizes active and public transportation. In regions that are already traffic-choked, putting a bridge on a “road diet,” (removing one or more lanes to give priority to bicycles, walkers, and buses) can seem like madness.

However, depending on location and length, a bike lane across a bridge can lead to benefits to both traffic patterns and businesses. For example, the Burrard bike lane in Vancouver, BC created controversy when it was introduced in 2009. Detractors believed removing a lane from the busy bridge would lead to horrible traffic jams in the area. These fears were not realized. Instead, the bike lane became one of the most successful in North America. Over one million bikes cross the bridge each year, and vehicle traffic still moves freely. Although it is hard to know which riders would have driven if a safe lane were not available, the increase in cyclist trips outstripped even generous projections. Perhaps this is why the feared traffic-tied outcome did not come to pass. The once skeptical president of the Downtown Business Improvement Association, Charles Gauthier, now endorses the lane, suggesting “We couldn’t have predicted how popular cycling would become if you made it safer for people.”

The Business Improvement Association may also be reacting to an improved business outlook. Research on cyclist spending habits in Portland, Copenhagen, and France have all shown more retail spending than their car-driving counterparts. This pattern makes the business case more compelling for local merchants.

Of course, not all bridges link residential districts to business and retail districts. Many bridge spans are part of highway systems connecting far-flung regions. Yet distance cyclists are out on interstate routes for bike tourism or exercise. Cyclists will often ride on the highway’s shoulder. Bridges, without wide shoulders for cyclists to travel on, are much safer for all users when they provide a separated cycle path. For bridges that see few cyclists per month, these are often narrow two-way paths on one side of the bridge, perhaps also shared with pedestrian traffic.

Public transit: bus lanes and rapid transit across bridges

Public transit also accesses bridges, both within cities and interstate. Marked bus lanes are more commonly found within cities. These transitways are useful on bridges that suffer congestion during rush hours. Dedicated bus lanes are less common in rural or interstate highways.

In some locations, road-rail bridges (also known as combined bridges), often combine rail and vehicle traffic. The Sydney Harbour Bridge in Sydney, Australia is a combined bridge that has a walkway, a cycleway, a dedicated bus lane, passenger light rail, and eight vehicle traffic lanes.

Jump protection

Unfortunately, bridges have had a painful history of being used in suicide. For many years, it was assumed that those who were thwarted by fences or nets on a bridge would find some other way to injure themselves. If the way they chose involved a gun or car they might cause other deaths. It was not a public health priority to create bridges that would structurally prevent these unfortunate actions. Instead, energy would go to helping those poor souls who found themselves at the bridge’s edge.

However, recent research into “coupling” has turned this theory on its head. In Malcolm Gladwell’s “Talking to Strangers,” he rounds up statistics that show that ease-of-access to a specific method can make a big difference to whether an individual takes their own life. This new understanding, and a public-health perspective, suggests that fences or nets on bridges will save lives.

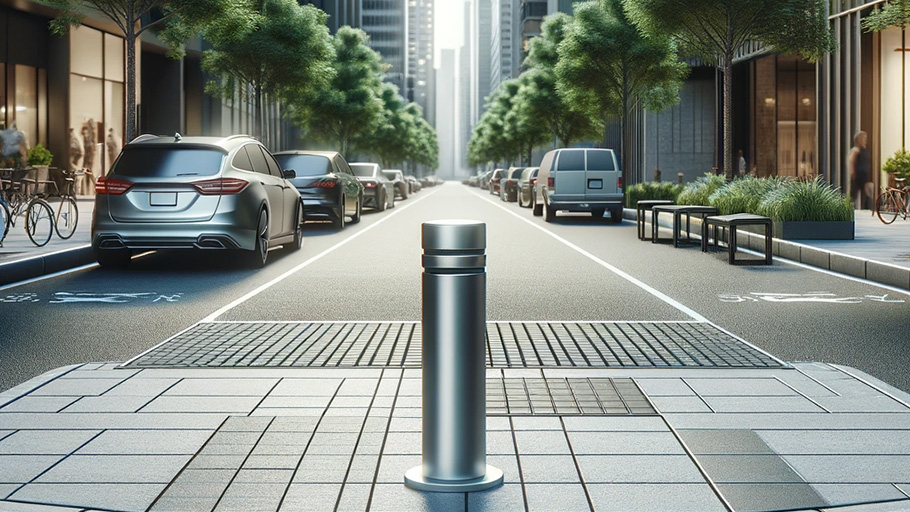

Bollards and bridges

Bollards started out on docks and marinas, as a place to moor a ship. Bollards and bridges have therefore had a long history of close proximity. Although bollards are still used as mooring posts, inland bollards around bridges are likely to be involved in traffic management.

The City of London made news for installing anti-terrorism bollards on London Bridge to protect the pedestrian and bike lanes. The barricades are somewhat jarring in the historic district. They’re long, black, lozenge-like objects bolted together so that they provide crash support. These were chosen in part because they could rest on the existing path without major modification. When pouring new concrete, however, anti-crash cores can be installed and covered with more classically designed bollards like the R-7585, to provide both protection and to support the aesthetic of a place.

New York City, and Manhattan in particular, is dependent on its bridges. According to a 2016 report by the New York City department of Transportation, 2.6 million people use the 47 toll-free bridges in NYC every day. Managing this volume of traffic over bridges is strategic: it’s not just the bridges themselves, but the arterial roads and traffic patterns leading up to the bridge, and the infrastructure built around the bridge that help keep accidents and frustrations low.

One of the ways that New York manages traffic is using bollards on the approach to the bridge. A 2007 report called “Rethinking Bollards” explains the use of flexible bollards to separate turn lanes from through traffic at bridge and tunnel access points. They are also used to create contra-flow lanes on bridges. In addition to channelizing via flexible bollard, New York protects the tight-turn corners on the approach to the bridge deck with Martello bollards, a specially-designed sloped bollard that captures the wheels of vehicles that cut in too tightly, and returns them to the street. Martello bollards are installed for several blocks around the lead-in to the Brooklyn bridge.

Economic value of bridges

Advances in infrastructure have historically supported economic advancements, and bridges are integral to a well-connected network of infrastructure. Trucks and trains rely on bridges when moving goods inland. When bodies of water stop being an impediment, both trade and workers can move through the region. This integrates separate parts of the economy.

Bridge infrastructure is in serious need of care across the country. Attention to this necessary work represents an opportunity to optimize for the future. In the past building more roads and opening more lanes was the primary role of infrastructure support. But in a world where space is a premium, more does not necessarily mean better. Excellent traffic management on bridges and active transportation supported throughout the network can help a busy city work efficiently and safely—while enriching the economy, the street life, and the sense of place.