See the green sand casting process

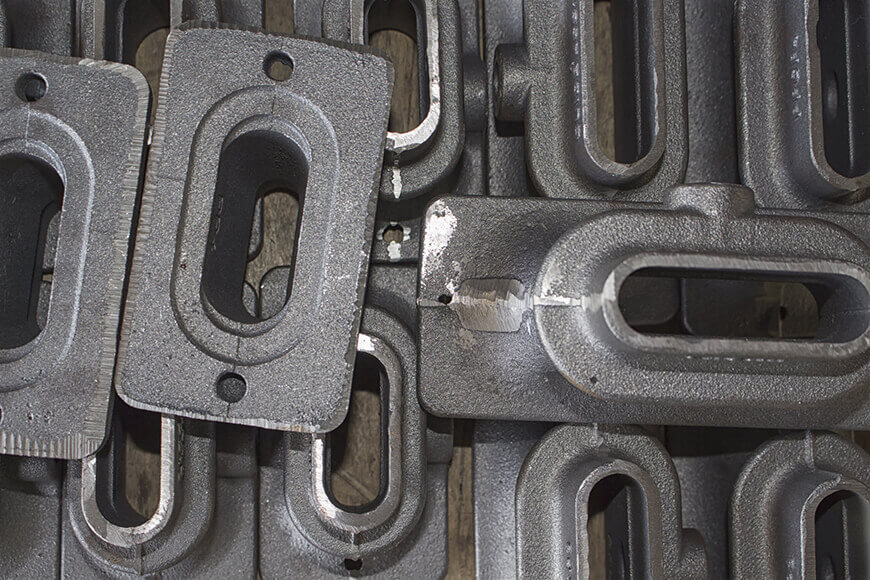

Although there are many types of metal casting, sand casting is by far the most commonly-used type.

The process sounds deceptively simple. A replica of the desired metal item is pushed into foundry sand, where it creates a hollow “negative” of the object. That void is filled with molten metal, capturing its details. When the void cools, the metal object is pulled from the sand, with the original design faithfully captured.

Anyone who has built a complex sandcastle or sand sculpture has some experience with how sand can be good at capturing small designs. As well as being pliable, sand is inexpensive and resilient in the high heat conditions necessary for metal casting.

The basic premise of sand casting

Sand casting can be done into any earthen space that will hold its shape around molten metal. In this video, liquid aluminum is poured into an abandoned fire ant nest. After the metal cools it is unearthed and cleaned, and the resulting casting has captured the shape of the habitat.

Artist creates sculpture by sand casting into an empty ant hill

When the ants built their nest, they were relying on the same qualities that sand casters do: well-packed grains of earth can create structure resistant to collapse. In this case, the habitat keeps form even when molten aluminum is introduced.

Sand casting: a skilled craft

Of course, fire ants do not create spaces with casting in mind. During “in the wild” sand casting, there will be issues with escape of gasses from the mold, the permeability of all parts of the habitat, and the rate of cooling in each chamber. Areas of the metal maybe be weakened due to differential rates of cooling—which is irrelevant to an interesting and attractive art piece that will not bear a load.

However, metal structure and weakness are relevant to industrial castings that will deal with mechanical strain, such as engine parts and building elements. It is handling these aspects of metallurgy that make sand casting reliant on precise techniques and expertise.

To begin the process of sand casting, the foundry sand is prepared in mullers, which mix the sand, bonding agent, and water. Aerators are used to loosen the sand and make it easier to mold. Sand cutters, that operate over a heap on the foundry floor, may be used instead of mullers. Delivery of the sand to the molding floor may be by means of dump or scoop trucks or by belt conveyors.

At the molding floor the sand is formed into molds; the molds may be placed on the ground or delivered by conveyors to a pouring station. After pouring, the castings are removed from the flasks. Adhering sand is removed by a shakeout station. The used sand is returned to the storage bins by belt conveyor or other means.

There is a huge variety of equipment and methods available to the foundry. These range from simple, work-saving devices for foundry workers, to completely mechanized units that do everything from molding to shakeout. What level of automation a foundry uses is based on the economics of the production line. A company producing thousands of similar parts, like an automotive manufacturer, may use more automation than a “jobbing” foundry that does smaller runs of very dissimilar parts.

Whether automated or not, foundries use the same types of tools in sand casting production. A flask is a rigid frame used to hold the sand which forms a mold. Flasks generally consist of two parts: the upper section, called the cope, and the bottom section, the drag. When more than two parts are used, the intermediate sections are called cheeks. In many foundries, this flask is set on a “bottom board.” This board is used so that as the flask is removed the mold can still be moved around for pattern removal, pouring, and other important steps.

Foundries use three versions of flasks: tight, snap, and slip. Tight flasks remain in place while the mold is filled with metal. Snap flasks are hinged on one corner and lock on the opposite diagonal corner. Molders unhook and remove these flasks after they close the mold. Slip flasks are of solid construction and taper from top to bottom on all four sides: they slide off a closed sand mold easily. Snap or slip flasks permit the molder to make many molds with one flask.

Before pouring snap- or slip-flask molds, a wood or metal pouring jacket is placed around the mold and a weight set on the top to keep the cope from lifting. The cope and drag sections on all flasks are maintained in proper alignment by flask pins and guides.

Flasks may be filled with sand by hand shoveling, gravity fed from overhead hoppers, loaded by a continuous belt from a bin, or filled tightly with mechanical sand slingers. Very large molds may be filled by an overhead crane equipped with a grab bucket.

Hand ramming is the simplest method of compacting sand. To increase the rate, pneumatic rammers are used. The method is slow because the sand is rammed in layers, and it is difficult to gain uniform density. More uniform results and higher production rates are obtained by squeezing machines. Hand-operated squeezers were limited to small molds and are now obsolete. Air-operated machines work for larger molds and are also much quicker. Squeezer molding machines produce the greatest sand density at the top of the flask and softest near the parting line of pattern.

In jolt molding machines, the pattern is placed on a plate attached to the top of an air cylinder. After the table is raised, a quick-release port opens, and the piston, plate, and mold drop free against the top of the cylinder or striking pads. The impact packs the sand. The densities produced by this machine are greatest next to the parting line of the pattern and softest near the top of the flask. As a separate unit, it is used primarily for medium and large work. Where plain jolt machines are used on large work, it is usual to ram the top of the flask manually with an air hammer.

Jolt squeeze machines use both the jolt and the squeeze procedures. The plate is mounted on two air cylinders: a small cylinder to jolt, and a large one to squeeze the mold. These are widely used for small and medium work, with match-plate or gated patterns.

Sometimes, pattern-stripping devices can be incorporated with jolt or squeezer machines. These machines remove the pattern from the mold automatically. Pattern removal can also be accomplished by using jolt-rockover-draw or jolt-squeeze-rollover-draw machines. These machines vibrate the mold to allow the pattern to be more easily withdrawn: the kinetic energy of the vibration moves differently through the sand than through the metal and helps the components part. Rollover draw machines flip the mold upside down to let the pattern fall away more easily. Rockover machines tilt the mold but do not go as far.

The sand slinger is the most widely applicable type of ramming machine. It consists of a rotating pump called an impeller that sits on the end of a double-jointed arm. This arm has conveyers mounted upon it which feed sand to the impeller. The impeller rotates at high speed and gives the sand the velocity to ram tightly into the mold on impact. The head of the machine may be directed to all parts of the flask. This can be done manually on larger machines or automatically controlled in high-speed production lines for smaller molds.

Vibrators are used on all pattern-drawing machines. These free the pattern from the grip of the sand before removal. Their use reduces mold damage to a minimum when the pattern is extracted and has the additional advantage of producing castings of more uniform size. Vibrators are usually air-operated.

Small castings may be poured by using stackmolding methods. In this case, each flask has a drag cavity molded in its upper surface and a cope cavity in its lower surface. These are stacked one on the other to a suitable height and poured from a common sprue.

Metallurgy and the maker movement

Early metallurgists cast bronze and brass in small operations of a few artisans. Then, over the long period of the Iron Age, and continuing through the Industrial Revolution, foundries became large operations specializing in managing the extraordinarily high temperatures needed to make steel and iron castings and keeping up with the production demands of a growing economy. Recently, there has been a movement to reclaim traditional manufacturing skills. Hobbyists with home foundries use metals with lower melting temperatures than iron and steel due to safety and complexity concerns, but many of the steps they take are the same. Watching the process come together can demystify casting work.

YouTube creator The King of Random demonstrates aluminum casting in this short video of his at-home Mini Metal Foundry. For most of his castings, he is using a “Foam Casting” method, a form of investment casting where a polystyrene shape is buried in loose playground sand. At 6:42, he shows how green sand casting produces a nicer surface finish. The wooden container he is using forms a “tight flask”.

King of Random demonstrates casting with his home metal foundry.

One of the important aspects of this video is the focus on safety. We see how spalling can happen when hot metal pours on concrete: an incredibly dangerous accident that is the reason why many foundries are designed with dirt floors. Metal casting is interesting and fun, but the risk of serious injury is high.

Sand casting: an innovative tradition

Foundries have been manufacturing metal objects for millennia, and during that time, the basic premise of sand casting has stayed the same: pour metal into a void made of well packed grains of sand. Sand cast objects are ubiquitous in the industrial age: an important part of most industrial machines, engines, and many architectural fittings. Yet the industry has been innovating to help increase safety, size, consistency, and speed, and this form of manufacture undergirds the innovation of inventors and designers creating the technologies of tomorrow. Sand casting is then an interesting set of paradoxes. It is a process that seems simple but takes complexity and craft to perfect. It is both one of the most traditional skills and a site of constant, ongoing innovation. It is no wonder that today the work of the foundry is being rediscovered by hobbyists and the curious, looking to understand the history of the objects we use every day.