Industrial wheels demonstrate how to design for the long haul

Once upon a time, most machines were built to last a lifetime. Moving parts were expected to wear, but repair was an expected part of the life cycle. Trends and innovations might arise that would be more appealing but there were always those loyal to their original choice. For the direct-to-consumer sector, these days have largely passed. A study from the National Association of Homebuilders shows that most appliances now have an expected lifespan of ten years. Planned obsolescence is both a function of expected product development. Yet this business method creates concern for the environment and for resource exhaustion. People are looking for other ways to purchase and sustainable manufacturers to purchase from. Tried and true historical approaches to manufacturing, including planned longevity and right to repair, can support the conversation on planned obsolescence vs. sustainability.

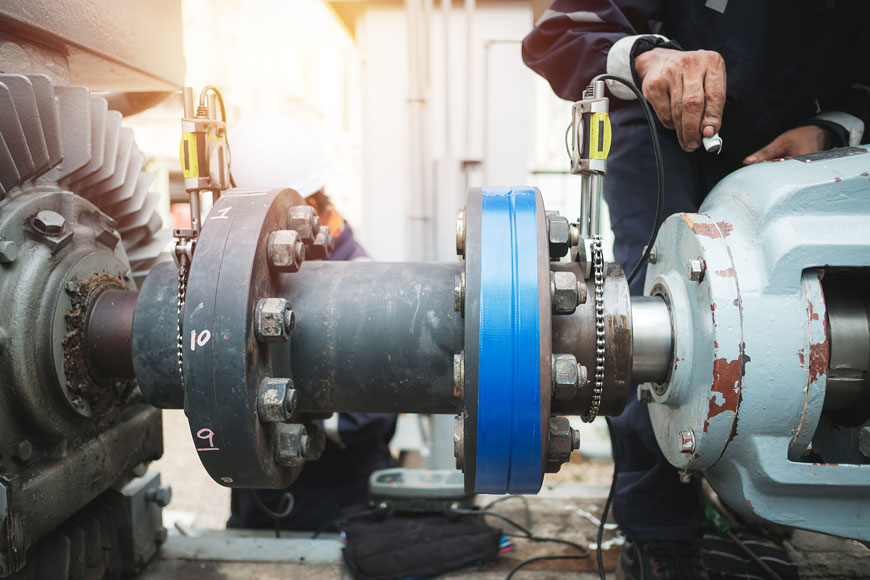

Commercial and municipal products fare a little better than consumer goods. Industrial machines usually have an intense workload. Companies are willing to pay more for systems engineered to last as long as possible.

Our industrial wheels, designed to work with rail systems, are one such product. Not only do they take years to wear out even while under stress and strain, they are often chosen to counterbalance the wear and tear to the rails they run on. Product lines like these can help guide both retail businesses and consumers back to a more sustainable product life cycle.

What is planned obsolescence?

Companies plan obsolescence when they design a product with a limited useful life. This encourages the consumer to buy a replacement more quickly. The company may:

- Choose materials and manufacturing techniques that create a shoddier, breakable product

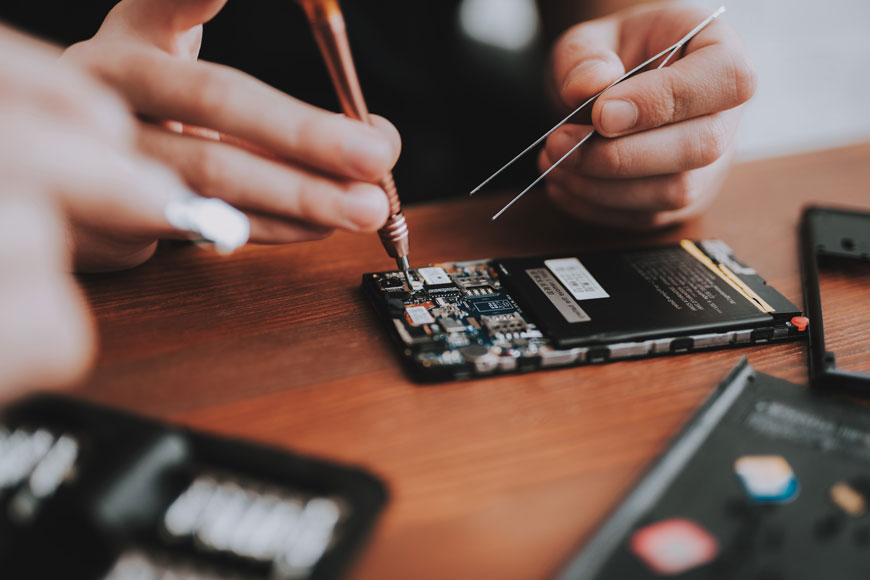

- Make the product impossible or cost-prohibitive to repair

- Create style choices that will have limited, temporary appeal

- Change the way people interact with the product so that previous versions become unusable

- Sabotage the product so it becomes less and less functional on the manufacturer’s timeline

High-replacement goods are often—but not always—made with cheap materials so they can be offered at a lower price point than well-made goods. For this reason, it is often cheaper for the consumer to replace the item than to try to fix it. Replacement parts are not available, and even if they can be found, the labor to do the repair is often not available or is so expensive that it’s cheaper to buy new.

Although high-replacement goods used to be inexpensive, planned obsolescence has made its way into high-end or status goods. Shoes, appliances, and even motor vehicles have a shorter lifespan. In the case of technology, there have been several companies, like HP with their printers and Apple with their iPhones, who have programmatically limited the functioning of their products even if the materials still work as intended.

Sustainability vs. planned obsolescence

Sustainable economies have their carrying capacity balance their consumption. There are many ways to balance these input and output requirements. The circular economy, which focuses on reuse, repurposing, and re-cycling, is one way to increase the carrying capacity of an economy. Designing durable products again is a way to reduce consumption, specifically with respect to replacement due to wear.

Relearning sustainability

Consumers and companies are prioritizing sustainability for economic and environmental reasons. To ensure a product will withstand intended use, manufacturers consider:

- Materials: choosing constituents that will stand up to intended use

- Engineering: resilience and durability should be a primary concern

- Repair and replacement: working components should be replaceable

- Backward compatibility: new designs should work with old systems

- Reuse and recycling: support the circular economy by minimizing reliance on extraction

We are proof that creating strong, durable products is a viable business model. Our wheels, bollards, and hardscape are not designed for short product lives.

- Materials: metal is a tough, durable material. It has an incredibly long service life when maintenance and safe working loads are observed.

- Engineering: Working components, like double-flanged wheels, are designed for resilience and durability.

- Repair and Replacement: If a wheel fails, it can be swapped out in a system without overall machine replacement. Similarly, scratched bollards can be resurfaced.

- Reuse and recycling: metal is the easiest material to recycle and can be reused infinitely with no loss of quality. When properly melted, scrap metals create alloys just as good as those made with virgin ore. Steel made with scrap conserves 1400 pounds of coal and 120 pounds of limestone.

- Backward compatibility: customization allows foundries to produce components for original machines.

Challenges for the consumer marketplace

The issue for many consumers is that sustainable products often have a higher upfront cost. In a time when budgets are strapped, this can be a frustrating issue, especially when the durable product has a lower lifecycle cost.

Yet there are consumer brands that feature this sustainability at an accessible price point. Many metal-based products are naturally sustainable. Cast iron cookware has a well deserved reputation for longevity. If cared for, a cast iron pan can last for generations. Swiss Army Knives also have a reputation of being made to last, with a lifetime warranty against defects in material and workmanship. Sustainable companies also offer replacement or repair of breakable components, like offering replacement lids for water bottles.

It is not just metal products that offer sustainable practices. Saddleback Leather Wallets are notable for advertising their products as “over-engineered,” and offering a 100-year warranty. Over-engineering sometimes suggests that a product is more robust than necessary. Yet perhaps longevity will again become the new normal. New materials can also stand the test of time: with their foam construction, in 2014 Crocs clogs suffered sales slowdowns in part because they do not often need replacing.

Everything old is new again

Manufacturers traditionally took pride in creating sturdy products that lasted for years. Yet after the Industrial Revolution, there was a change in approach. Available electricity, automation, and transportation meant that products could move more quickly to market. These innovations encouraged fast replacement cycles.

Yet these rapid design-to-market systems allow quicker, less wasteful product development. Although these abilities have been used to support planned obsolescence, they can also be used on behalf of sustainability. Manufacturing advances allow us to more easily design custom objects or modify stock lines. Manufacturing can address specific consumer needs and create bespoke designs that last for years. The lessons from industrial manufacturing for longevity, as in our wheels and bollards, offer a view of a maintainable product cycle. Traditional practices, wedded to modern day innovation, create value in a sustainable future.