How cities are working to increase safety and access to cycling

Vision Zero is a program intended to bring traffic fatalities and serious injuries to zero. Municipalities all over the world are participating. Often, these same cities and towns are simultaneously trying to increase active transportation. The goal is to integrate pedestrians, cyclists, transit users, and scooters, without increasing traffic conflict. Transportation officials know that excellent road infrastructure reduces vehicle crashes. In a multi-modal city, this approach requires investing in “complete streets.” Safe bike infrastructure is an essential part of any complete street plan.

What is a complete street?

A complete street is accessible and safe for pedestrians, cyclists, public transit, and vehicles. It must fit into the neighborhood and traffic around it, so there is no single design. A complete arterial road will look different than a complete residential street. The arterial road might have traffic-controlled crosswalks, pedestrian islands, a protected bike lane, a bus lane, and curb extensions. A residential bike route may require cars and cyclists to share the road but have traffic diversions and roundabouts.

Bikeways

Bikeways are paths or lanes designated for cyclist use. Bikeways are the most common type of bicycle infrastructure, with many varieties, including:

- Conventional bicycle lanes

- Shared use and quiet street bike routes

- Painted buffer lanes

- Contraflow cycling lanes

- Protected bike lanes

- Cycle tracks

- Off-street bike paths

Although there have designated paths for bikes for as long as bicycles have existed, it took until the 1970s for transportation authorities to embrace cycling infrastructure as part of a comprehensive road strategy. In 1971, California State contracted with UCLA to design bikeways. The discussion around these designs led to a set of standards published in 1976.

Bikeway infrastructure has been evolving since then. Since 2010, the National Association of City Transportation Officials started looking at the success of cycling cities in Europe. Safety for all ages and abilities (AAA networks) is essential for widespread adoption of cycling. AAA networks limit cyclist exposure to cars through protected bike lanes, dedicated signals, and other approaches. Vision Zero mandates help see these users are protected as well.

Lanes for Bike Infrastructure

Shared use and quiet-street bike routes

“Sharrows” are arrows painted on the ground, with a bicycle icon, that suggest that vehicles and bicycles share the roadway. Their placement often points out the preferred location for bike traffic. Bikes should not press too closely to parked cars. Being “doored,” when a cyclist is hit by or runs into an unexpectedly-opened car door, is a very serious hazard that can cause fatalities.

Shared-use streets are bike-friendly routes. They may have sharrows or other painted markings but may also just be marked with signs. These routes are often part of quiet-street bike route networks. These streets are often residential rather than arterial. Usually, the street features other traffic calming features, like vehicle diversions that turn cars while allowing pedestrians and cyclists travel through. Where possible, these routes are placed under tree-canopied streets. Trees have a natural traffic slowing effect and provide cooler air to active travelers.

Conventional bike lanes

Most municipalities, starting in the 1980s, have been focused on providing conventional bike lanes. These lanes are usually between moving traffic and either parking or the sidewalk, and travel in the direction of traffic. They are usually marked by painted lines plus the symbol of a bicycle.

Painted bike lanes designate road space for the use of bicycles, but they often end up as a parking or stopping lane.

Painted buffer lanes

Painted buffer lines are road markings that create a “do-not-cross” zone beside a bike lane. As with conventional bike lanes, cars sometimes still park or stop in the lane. However, these buffers are quite useful where the bike lane is sandwiched between parked cars and the sidewalk. The buffer makes sure that opening passenger-side doors are not a hazard to cyclists.

Contraflow cycling lanes

Contraflow lanes are lanes where some cyclists are moving the opposite direction of the motor vehicles adjacent to the lane. Sometimes, this is done with a two-way bike path, with the bike lane adjacent to vehicles moving contraflow. Sometimes this bike infrastructure solution means putting lanes on either side of a one-way street, so that bikes move in both directions. The lane that moves in the opposite direction of oncoming cars is the contraflow lane.

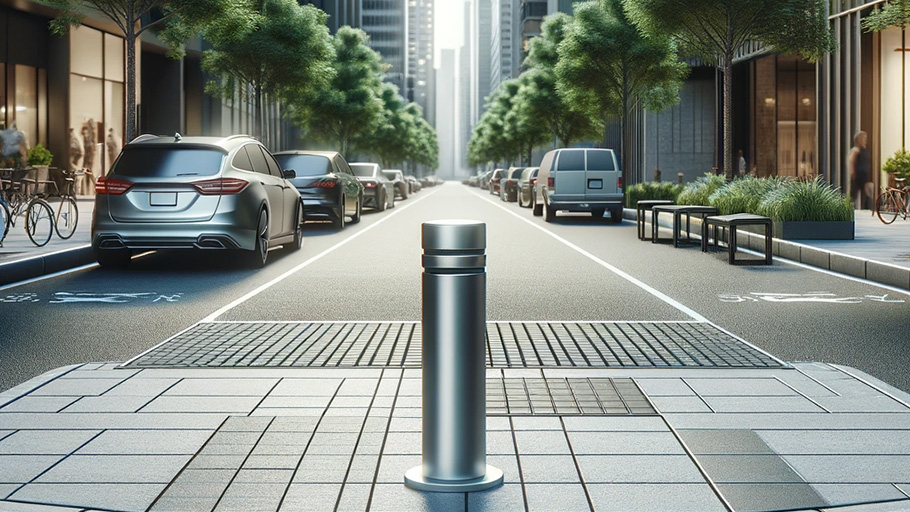

Protected bike lanes; separated bike lanes; cycle tracks

Protected bike lanes have a physical barrier between motor vehicle traffic and cyclists. The term separated bike lane is also used. Cycle track is sometimes used to mean separated bike lane, but sometimes means off-street tracks—either raised to be vertically separated or following non-vehicular routes.

Separation can be created in many ways. Commonly, there is lots of visibility maintained between the road and cyclists. Flexible, weighty bollards or plastic delimiters are used in spaces where emergency vehicles may need access to a curb. These attempt to discourage the bike lane’s use for parking, although plastic delimiters are often ripped free.

Fixed separators ensure that the bike lanes are separate. Medians, planters, jersey barriers, curbs, parked cars in a parking lane, bollards, and parking stops are all commonly used.

A large study from University of Colorado Denver and University of New Mexico showed cities with protected bike lanes had 44% fewer deaths for all road users.

Off-street bike paths

Off-street bike paths do not share pavement with vehicle traffic. These paths are often integrated into park space and offer a vehicle-free form of commuting. Off-street bike paths can be shared-use with pedestrians or may be specified as bike-only.

Cycling network maps

Creating bikeways is a good step towards encouraging biking in a community. Publicizing where those bikeways are is important for cyclist route planning. Most jurisdictions investing in bike infrastructure create cycling network maps so that people can plan before they head out.

As with vehicle directions, map applications like Google are available for route planning. Google has cycling and greenway maps complete with elevation planning and has invested time and resources into offering cycling options. As with any GPS, data must be used with caution and common sense as the information is not always perfect and local conditions may change.

Traffic calming and management

Traffic calming strategies

One way to create safety for cyclists and pedestrians on smaller streets is through a variety of environmental traffic calming strategies. Our complete guide to traffic calming introduces strategies like speed bumps and humps, chicanes, neckdowns, and more.

Road diets

Road diets remove the number of vehicle travel lanes on a street. This can also be called “road rechannelization,” because travel lanes are often turned into pedestrian, transit, or cycling space. Reimagining traffic flow is important to road diets. It’s not enough simply to turn a lane into a bike lane: rather, the needs of the overall network need to be considered.

For example, if the road has two lanes in each direction but many cars turn left in each case, moving to one lane may cause congestion as cars wait for a gap. Perhaps a central reversable left-turn lane can help through-traffic keep going.

Road diets reduce the overall crash frequency in an area even when they do not reduce traffic volumes.

Intersection management

Intersections are dangerous. When cars are turning, drivers must be aware of other vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists, all of whom may be coming from different directions. Users of all types can be confused about right of way. Some infrastructure improvements can lead to a false sense of security: research shows that “on multi-lane roads with volumes of more than 12,000 vehicles per day, having just a marked crosswalk was associated with higher pedestrian crash rates when compared with unmarked crosswalks.” (Federal Highway Administration.)

55% of cyclist injuries and 28% of cyclist fatalities happen at an intersection. Making intersections safe has been one of the areas of focus in Vision Zero. For bikes, there have been two common infrastructure developments.

Advanced stop lines (Bike boxes)

Advanced stop lines create a space for bicycles to stop ahead of cars at intersections with traffic signals. Awareness campaigns are necessary for their use: many cyclists are hesitant to take the space.

However, cyclists are more visible to cars and transport trucks in this location. They are less likely to be missed by right-turning vehicles. Research by the Portland State University showed that bike boxes reduced conflict between cyclists and cars, increased yielding behavior, and made both drivers and cyclists feel safer.

Changes to right-of-way and bike specific signaling

At busy intersections, right-hand turns can cause conflict for bikes in a curb-side bike lane. Some of these places offer a right-turn signal or prohibit cars from making right turns on red. These options are sometimes used with a bike box.

In some areas with bike contra-lanes, cyclists have their own light. while one direction of vehicle traffic has an advanced left turn away from the bike lanes, two-way bicycle through-traffic can move through the intersection. The advanced left turn and the bicycle traffic are both then stopped. Then right-turning drivers can safely cross the bike lane.

Bike sharing

As cycling infrastructure increases, cities are moving to an implementation of bike-share. When cyclists can rent and ride one-way, bike share can be a commuting option that converts some trips from car or transit. Analysis of NYC’s CitiBike shows benefits to end users and to the city. Generally, bike-share is used by inexperienced cyclists and tourists and are therefore use is supported by AAA networks.

Cost to build bicycle infrastructure

Good, safe, and inclusive bike infrastructure is not inexpensive. Country-wide, it costs between $133,170 and $536, 680 per mile to build protected bike lanes on major streets.

However, the savings are big in health benefits and economic stimulation. More importantly, they help municipalities reach Vision Zero, by reducing traffic fatalities for all road users.

Innovative infrastructure

Bike Tunnels

In many places bicycle tunnels are used to dip beneath fast moving traffic above. In Davis, California, there are many different tunnels connecting bike routes. They’re so well regarded in the city, each with its own personality, that they have their own entry in the local wiki page.

Hovenring

The Dutch have many innovative bike-inclusive traffic designs, leading to the country being one of the most bike-friendly nations in the world. Even for the Netherlands, though, the Hovenring is something special. Held aloft above the highway on a series of cables, this cycletrack allows riders to pass above the vehicular fray.

Berenkuil

Berenkuil means “bear pit” in Dutch. It’s the opposite of the Hovenring, in which traffic is put onto raised roads or bridges above grade so that cyclists and pedestrians can move underneath. Similar to bike tunnels, a berenkuil solution normally allows movement in many directions under an intersection.

Rail to trail conversions

In many places across North America, unused railway lines are being converted to bike and pedestrian off-road trails. Many of these rail-to-trail conversions are used recreationally by hikers, joggers, and cyclists—but in some areas they become popular commuter routes as well. One such is the Monon Trail in Indianapolis, IN, which sees 1.3 million users per year.