Changing sedentary lifestyles by enhancing walkability

North American society is experiencing an epidemic of sitting. Reviews of current research show that, even in active, otherwise healthy people, sitting increases the risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The metabolic shifts are so prominent some researchers are calling the effects on Western populations “the sitting disease.” We all need to move, but technology has made it much easier to stay connected from the comfort of our chairs. Work and school often require being seated in an information economy. Leisure time increasingly means being on the couch, playing with technology or watching TV.

Transportation is about the movement of people, yet it is still often a sedentary activity. In many cities, driving is more convenient than other forms of transportation. Car-focused streets turn what could be an active part of our days into another time that we are seated. This not only impacts public health, but also the vibrancy of our street-level spaces.

Therefore, city planners and landscape architects are important to a public health push-back against sedentary lifestyles. The geography of our cities shapes our community experience and can motivate movement as part of a daily routine. Active design guidelines create walkable cities.

What is active design?

According to the Center for Active Design, “Active Design is an approach to the development of buildings, streets, and neighborhoods that uses architecture and urban planning to make daily physical activity and healthy foods more accessible and inviting.”

Active design strategies are used to support healthier lifestyles. Human environments have changed since we spent our days roaming arid grasslands in the hunt for migrating wildebeests, but our bodies are still evolved for that long-ago lifestyle. Modern streetscapes prioritize vehicles for short trips. Our parking is arranged to be close and convenient, and buildings, elevators and escalators are standard for moving us between floors.

This isn’t to say that these were bad designs: for some people, such accessibility is vital and opens the streetscape. Yet in dealing with the realities of the 21st century, organizations like the Center for Active Design are looking for ways to advance our urban landscapes and encourage more physical activity.

An epidemic of sitting

Research in the Annals of Internal Medicine suggests that the average American sits for at least 10 hours every day and this sedentary behavior leads to metabolic change and increases health risks. Health research overwhelmingly shows that even small lifestyle changes in physical activity make a difference to these risk profiles.

Active design guidelines do not require people to make a major overhaul to their lifestyles. Although there are definite health benefits to regular, vigorous physical activity, not everyone is an athlete. Creating an environment that makes movement fun, safe, and accessible invites everyone to make small and sustainable lifestyle changes in an enjoyable way. We don’t need to run marathons to be healthy, but we do need to spend more time moving ourselves under our own power.

Cities can encourage movement by becoming walkable. An active commute, a stroll at lunch, errands run on foot: these little activities can help people sit less in pleasant, almost unobserved ways.

Design for walkability

If we want to encourage walking, we need to know what makes people walk. New York City’s Active Design Guidelines identifies five design qualities “critical to a good walking environment”:

- Imageability is the quality of a place that makes it distinct, recognizable, and memorable. A place has high imageability when specific physical elements and their arrangement capture attention, evoke feelings, and create a lasting impression.

- Enclosure refers to the degree to which streets and other public spaces are visually defined by buildings, walls, trees, and other vertical elements.

- Human scale refers to a size, texture, and articulation of physical elements that match the size and proportions of humans and, equally important, correspond to the speed at which humans walk.

- Transparency refers to the degree to which people can see or perceive objects and activity—especially human activity—beyond the edge of a street.

- Complexity refers to the visual richness of a place. The complexity of a place depends on the variety of the physical environment.

- Effective traffic calming can also be a key strategy to ensuring safe walking environments.

What does this look like at the community level? Let’s look at both large-scale, city-wide planning and small-scale site design.

Walkable cities and community planning

On a large scale, infrastructure can encourage active transportation in the form of walking, running and cycling. This can be achieved by increasing density (i.e. the walking distance between destinations) and improving the design and diversity of neighborhoods (i.e. the walking experience and the destinations themselves).

Increased density can be associated with smaller living spaces, but it also means shorter walking distances between destinations. People are more inclined to walk if it’s the most accessible and convenient means to getting where they need to go. We visit grocery stores, news and entertainment hubs, green spaces and goods and service providers daily. Access to healthy foods is also a prime component to effective active design—encouraging not only healthy activities but also healthy eating. Well-considered public transit in less dense areas also encourages walking. Riders may be inactive while on the bus or train, but 29% get their recommended daily activity by walking to and from transit.

Ultimately, when designing for active streets and community recreation, the user’s experience is what makes or breaks a concept.

Active site design: small scale design for walkable neighborhoods

When it comes to smaller-scale projects within a larger community, architects and designers can look for ways to reinforce, complement or even initiate local design principles.

Going back to the design qualities that are “critical to a good walking environment,” we see that user-oriented design is key.

Plants, vistas, and public art are all important aesthetic elements. People look to interesting sights to draw their attention, whether it be a statue or an inviting vantage. Texture and color in murals, gardens, trees, architecture, and site furnishings also make areas stand out and/or complement their surroundings. Giving users plenty to see—and strong sightlines to see them—are crucial to communicating a site’s possibilities.

Arrangement can also affect experience. It can mean the difference between a breath of exhaust in the midst of a noisy traffic environment and a breath of fresh air amidst a canopy of surrounding shade trees. Here’s a look at a few active design strategies.

Create an enticing destination

There are many ways to make a location more attractive to visitors. Aside from proximity, basic amenities such as water fountains, news boxes and public seating encourage and attract visits. What sorts of amenities are provided often helps dictate the space. Large fixed tables in a park can encourage picnics, smaller ones might invite chess players. Having washrooms available encourages a longer stay. Playgrounds draw families and off-leash areas encourage dog owners to drop by. A nearby place to buy coffee or ice cream can make an area a destination for breakfast or for dessert in the evening. Open spaces are attractive for people; these can be as wide as a field that encourages frisbee or a game of catch, or as small as a few folding tables near a food truck. People need space to relax and interact.

Destinations tend to grow more attractive over time: as more people use a space, the more it becomes a draw for people-watching, meeting, and events.

Connect others

Individual sites can reinforce the design of their surrounding communities by recognizing where people come from and where they need to go. Access to parking is a traditional design requirement for new site developments, but access to transit is becoming more of a focus. We see building entrances and onsite pathways designed with better orientation and attention to transit routes. These routes may require supporting elements such as crosswalks, protected areas and lighting.

For denser areas with heavy foot traffic, offering wayfinding elements can be a way to improve walking experiences within a broader community. Cities are typically designed to help drivers find their way—directing them to major highways, airport routes, lane cues, etc. Often, pedestrians are left to their own devices to find their own routes.

Provide options

Providing a choice-rich environment can be a means for creating a more diverse stage for activity and interaction. Stairs can provide more intense physical activity, but on their own, can be intimidating and repel users. To encourage stair use, proximity and connectivity are key incentives. If stairs are the quickest, most convenient means to getting to a destination, people will use them.

Staircase design can also affect usability. Riser and tread dimensions can look less inviting when they present a steep obstacle to climb. More gradual inclines with regular intermittent landings are more inviting. Tread textures and well-placed handrails also help ensure safe access.

Stairs may also offer a vantage point for users. The opportunity to see a well-designed site from a higher level might be enough to encourage users to step up on their own.

Support cyclists

Cycling is becoming a more prominent means for active transportation and recreation, and cities are making an effort to accommodate riders with improved infrastructure.

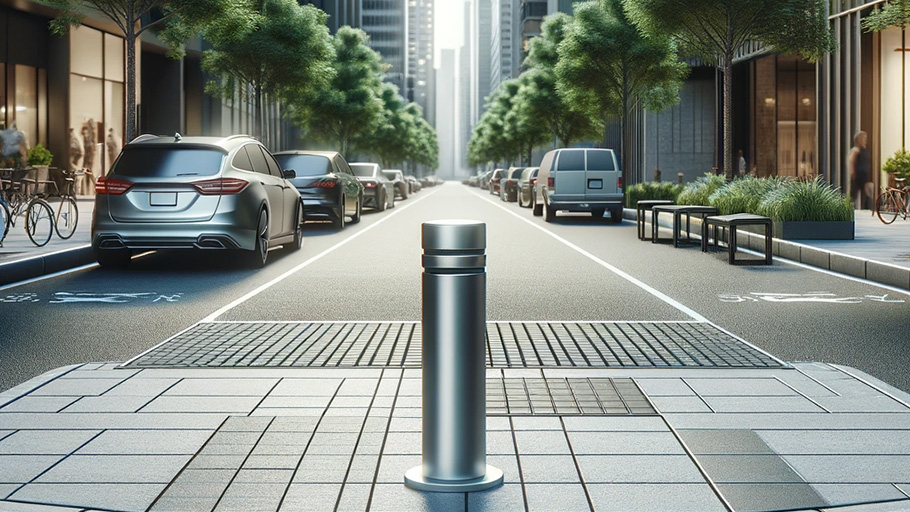

Research shows that cycling infrastructure is important to encourage new riders in urban environments. AAA or “All Ages and Abilities” cycling routes provide safety to inexperienced riders and increase the ridership in a region. These routes are separated from vehicle traffic through separated bike lanes and off-street or dedicated paths. Separation can come from planters, raised sidewalks, or bollards—either a durable flexible model, or of a more traditional design.

It is not only important to separate bicycles and cars. To create walkable neighborhoods, there must also be separation between cyclists and pedestrians. Again, raised or curbed lanes, bollards and planters can be used to help create comfort.

AAA design for cyclists also suggests smooth riding surfaces, grades less than 3% when possible, and excellent bike parking available at all major destinations, not just transit hubs. Along bike routes, inclusion suggests having bike parking at regular intervals so that people can stop to stretch or refuel.

Create pedestrian safety

According to a national survey, one third of Americans report not taking a walking trip in the past week. A major reported factor is safety.

In some cities, especially in residential areas, people may feel vulnerable due to lack of sidewalks, safe crosswalks, and poor lighting. Having safe destinations within walking distance is another factor: a small park, a public pool, or a corner coffee shop could spark more walking. When cities pay attention to sidewalks, lighting, and zoning they can create opportunities for active lifestyles even in low density residential neighborhoods.

In dense mixed-use neighborhoods, worries around walking safety tend to be about vehicle accident or attack. In these cases, design may need to be more defensive, including the use of bollards in vehicle zones, great lighting, clear signage, and traffic calming.

An environmental approach to “the sitting disease”

The arrangement, density, safety, and design of public spaces are key considerations for would-be walkers. Active design guidelines encourage people to move by addressing concerns and creating incentives to get out of the car. A considered interplay between local destinations, amenities, site furnishings, and gathering spaces can improve public health, community engagement, and the local economy by pulling people from their cars and putting them back into their neighborhoods.